A genius of the Victorian age

Who do you admire? A footballer? A Pop star? 150 years ago it was a man called Isambard Kingdom Brunel who was amazing the world with his skill and imagination. Brunel was an inventor, a designer and engineer who built not just bridges or tunnels or ships but all three!

In Victorian England he created structures and vehicles which to others seemed impossible. There's a good chance that you have travelled through a tunnel or crossed a bridge which Brunel built. Some people have called him the Greatest Briton ever. What do you think?

Born into the family business

Isambard Kingdom Brunel was born in Portsmouth on 9th April 1806. Brunel’s dad (Sir Marc Brunel) was a famous French engineer and from an early age Isambard was encouraged to get involved in the family business.

Starting at the very bottom

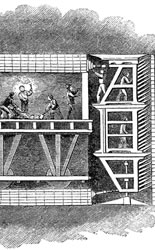

Brunel got his first big engineering job working for his father as Chief Engineer on the Thames Tunnel.

The tunnel would make it much quicker for trains to move around London and it was a very important project. But it wasn’t a nice job. At the time, most toilets in London emptied into the River Thames, which seeped into the tunnel making it smelly: very smelly, and very dangerous.

The tunnel collapsed several times when it was being built, killing many workers. Brunel himself was almost killed when a tunnel he was working on was flooded after its sides gave way. By a stroke of luck he was washed up a stairway and rescued.

Brunel never fully recovered from the accident and work stopped on the tunnel for several years. However, the tunnel was finally finished in 1828 and is still used today.

Building bridges

After working on the Thames Tunnel, Brunel left his father’s company and started working on his own, designing and building railway bridges. His first project was the Royal Albert Bridge over the Tamar River near Plymouth. In the next few years he designed lots of railway bridges, including the Maidenhead Railway Bridge which was the largest arch made of bricks in the whole world. Each span is a whopping 39m wide.

However, Brunel’s most famous bridge is the Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol.

In 1829 some wealthy merchants held a competition to design a bridge which could span the 200m gorge, standing over 60m above the river. Brunel put in four designs. All of them were rejected. Instead, one of the competition judges, a designer called Thomas Telford, won. This was very unfair and after people complained a second competition was held in 1830. This time Brunel’s design won.

Brunel never saw the bridge finished, he died before it was completed. It opened in 1864, five years after Brunel’s death.

However, he did build the towers at either end. The towers are now famous for their simple, classic design, but originally Brunel wanted a giant golden lion built on top of each one, in the style of Ancient Egypt.

Have you ever wondered how they began the bridge? The answer is very simple. Having built the two towers, the engineers carried a rope down one side of the gorge and up the other. To do this the rope needed to be over a mile long! They then stretched the rope tight and started work.

Paddington Station

In 1849 Brunel was asked to build the new Paddington Station for the Great Western Railway Company. In 1851 London was to hold ‘The Great Exhibition’ and Brunel was asked to design a station which would impress the thousands of tourists who would be visiting London for the event. Typically he didn’t design a station like the dark, gloomy stations of the time. Instead he took inspiration from the glass exhibition centre in Hyde Park nicknamed ‘the Crystal Palace’. Like the exhibition centre, Brunel built the roof of the station out of steel arches with glass panes in between them. At the time, no other stations had been built this way; Brunel had proved his genius as a designer.

The Great Western Railway

Today we take railways for granted, but 150 years ago they were a new and exciting way to travel. In 1835 Brunel was put in charge of building a railway line from London all the way to Bristol. It was his greatest challenge yet. The track was to be more than 100 miles long and Brunel planned every mile of the route himself. He used the skills he had learned when building the Thames Tunnel to design many tunnels, bridges and viaducts, including the famous Box Tunnel, through Box Hill near Bath. The tunnel was over a mile long (the longest in the world at the time) and rumour has it that on one day of the year, Brunel’s birthday, the sun shines straight through it.

As well as the huge engineering problems to be solved, Brunel also had to get wealthy land owners to allow him to build the railway line through their land. Most upper class Victorians didn’t want noisy, smelly railways running through their country estates. Lord Wellington (of Waterloo fame) said the railway was a bad idea because '... it will only encourage the lower classes to move about...'

ss Great Britain

As if designing bridges, stations, viaducts and tunnels wasn’t enough, Brunel was also one of the most revolutionary ship builders in the world. In the 1830s, the only way to get to America was on a sailing ship, which took more than a month. In 1836 Brunel formed the ‘Great Western Steamship Company’ and started building ships not powered by sail, but by steam engines. This allowed them to travel much faster. His first ship, the Great Western, reached America in just 15 days.

His next ship was even more ambitious. The problem with steam powered ships was that they needed to carry a lot of coal. So Brunel decided that, if his ships were to be successful, they would have to be big. The ss Great Britain was almost 100m long. It had a hull made of steel (the first in the world) and a single propeller at the back, unlike other steam ships which had wooden hulls and paddles.

The End

Brunel nearly died in 1843 when, whilst performing a magic trick for his children, he swallowed a coin and nearly choked to death. Luckily, he had designed a machine for shaking objects out of people’s throats which he used to try and remove the coin. Unfortunately it didn’t work, but he was eventually saved when his children hung him upside-down.

Sadly in 1859, Brunel died of a stroke. He was just 53 years old. He left a wife and two children, one of whom went on to become an engineer, just like his father and grandfather.